West Eden is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by Peter Yuill.

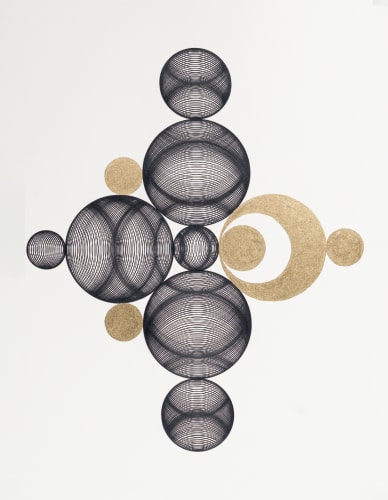

On view from June 29th to July 27th, this exhibition will mark the artist’s first solo presentation in Thailand. Featuring intricately hand drawn geometry, this thematic presentation of sacred geometry is an interpretation of deep mathematical connections that exist in a universe where mathematics, physics and astronomy are not mutually exclusive to spirituality. Yuill, who is known for precise drawings, pursues an articulation of the dichotomy between the divine, the random, the perfect and the absurd.

His upcoming exhibition with West Eden in Bangkok will bring together a series of new works that explore his fascination with the mesmerising moons and storms of Saturn. Yuill will also be presenting a large scale mural work that reflects his roots as a counter culture kid along with an associated multimedia screening of his process.

West Eden ยินดีนำเสนอ Celestial Symphony นิทรรศการใหม่ของคุณปีเตอร์ ยูล (Peter Yuill)

Celestial Symphony นิทรรศการเดี่ยวครั้งแรกในประเทศไทยของคุณปีเตอร์ ยูล ตั้งแต่วันที่ 29 มิถุนายน ถึงวันที่ 29 กรกฎาคมนี้ ศิลปินต้องการนำเสนอแนวคิดเรขาคณิตศักดิ์สิทธิ์ (Sacred Geometry) ผ่านรูปทรงเรขาคณิตที่บรรจงวาดด้วยมือทุกเส้น เพื่อสะท้อนความสัมพันธ์ของคณิตศาสตร์อันลึกซึ้งในจักรวาลที่คณิตศาสตร์ ฟิสิกส์ และดาราศาสตร์ ตัดขาดจากโลกแห่งจิตวิญญาณไม่ได้ ศิลปินตั้งใจเสาะแสวงความหมาย ทำความเข้าใจ และถ่ายทอดความสัมพันธ์อันซับซ้อนของสิ่งศักดิ์สิทธิ์ ความอลหม่าน ความสมบูรณ์แบบ และความไร้เหตุผล

นิทรรศการนี้ที่จัดขึ้นกับ West Eden จะจัดแสดงชุดงานที่ศิลปินได้ทำขึ้นใหม่ ด้วยแรงบันดาลใจจากความลึกลับของดาวเสาร์ (Saturn) ทั้งจากดวงจันทร์น้อยใหญ่และพายุหมุนหกเหลี่ยมซึ่งตราตรึงอยู่ในใจศิลปิน นอกจากชุดงานบนกระดาษแล้ว จะมีจิตรกรรมฝาผนังขนาดใหญ่และสื่อมัลติมีเดียแสดงกระบวนการสร้างงานที่สะท้อนรากเหง้าของวัฒนธรรมปรปักษ์ (Counter Culture) ซึ่งเป็นชนวนเริ่มต้นให้เขาหันเข้าหาศิลปะและยังคงอยู่ในจิตวิญญาณเขาเสมอมา

The Absurdity of Meaning - Peter Yuill (Artist)

This body of work is the culmination of a very long journey, as well as the embarkation of a new one, both personally and through my work as a painter these last 20 years.

I have spent several years working, progressively, through a deep, introspective exploration of all that makes me who I am, especially spiritually. To achieve improvement on my work, I concluded I would have to break myself down to absolutely nothing, so that I could rise again from a clear foundation. I began to study about my heritage, which connects me to Norse history and Norse paganism. I read the eddas and the myths which formed the building blocks of my family, and my deep connection to nature. I explored pagan beliefs, esoteric and occult practices; I read about the neo-pagan cults from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and a renaissance of spiritual curiosity that had long been stifled by the strict religious dogma of the church. I was inspired by Aleister Crowley's writing about philosophical freedom, and interconnectivity.

Through paganism I gained more clarity as to why I have always felt a deep connection with the earth and the cosmos. Growing up in Canada where I was surrounded by the wilderness, I allowed myself to connect with the spirit of the earth, even though I was never able to articulate it nor understand it. I started to realise that pagan beliefs as well as the major religions, not only Norse or European, but globally, were all tapping into this same feeling. Trying to explain what it was they felt, and why they felt it. A tipping point in my journey to re-approach my content and practice was reached.

From these occult influences, I started experimenting with sacred geometry; this led me into a deep fascination with resonance, frequency, and fractal mathematics and how these relate to sacred geometry. I concluded that sacred geometry and paganism/occult mysticism are an interpretation of deep mathematical connections that exist within the universe. This was a profound realisation to me at that moment, the understanding that mathematics, physics, and astronomy were not mutually exclusive to spirituality, but rather they were two sides of the same coin. I realised there were also two sides within me. My sceptical, logical and rational fact-based mind, and the deep internal feeling of spiritual connection towards my surroundings. I began distilling sacred geometry down, trying to analyse the core of it with deeper abstraction. With less reliance on standard and historic concepts, the relative abandonment of representational art and the pursuit of abstraction.

Using lines, the circular form and mathematics to meditate on spirituality and interconnectivity, I also became aware of the rising sense of existential absurdity. It is something I had always felt but had not been able to articulate. I started to contrast the divine, balanced and hypnotic circular form with a counter balance, flat black forms that shatter the illusion of reality and enforce the absurd reality of our limitations.

My painting process is also an articulation of the dichotomy between the divine and the random, the perfect and the absurd. It begins with working out a composition through roughs: I make miniature versions in up to 30 variations, trying out combinations, mixing and matching forms until I find the one that pleases me. Then I plot the composition on paper, using an assortment of drafting tools as well as templates of my own design. I draw the circular forms by hand, measuring all the angles and points through a geometric formula, not using a compass. A perfect sense of 3-dimensionality is achieved through these circular forms, a sense of volume, space, depth and movement created from overlapping lines. Then I shatter this impression of perfection by the imposition of flat geometric forms in black ink that bring us back to the reality that this is just a constructed 2-dimensional image. Yet this act is not meant as a denial of the sacred and divine: in fact the width dimensions of the flat black shapes are derived from the golden ratio diameter of the each of the circles. Rather than existing in separate realms, all these shapes speak to the spirituality of mathematics itself, to its presence all around us. Yet it is up to me how I use these formulas, how I relate to this presence, how I create my own life.

The absurdity lies in the perpetual question, "What is the meaning of life?" It's like screaming into the wind asking for an answer while knowing the answer will never come, and continuing to scream anyways. But rather than seeing this as a limitation, it became freeing for me.

In line with the philosophers Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Søren Kierkegaard, it was the point when I realised that there can never be a true understanding of our purpose. Not through thought, reason, or mathematics. To understand this, was to let go, and begin the next stage of existential development. To be truly free.

The balance between dark and light, black and white, yin and yang, have always been very attractive to me. Sharp contrast, depth, the desire to shed the colours of older work. I did not feel it was relevant anymore, it did not serve a purpose and was only a distraction. All that matters now is black and white. Creating depth and motion, tension and ease, movement and flow, form and shape, volume, all through the use of static line, circular form, and black shapes. All part of the process of shedding everything that is unnecessary. Distilling the image down to only what is important to the composition and the message, to what has meaning.

Geometric Abstraction:

The emergence of geometric abstraction as a pictorial language arose as a logical culmination of Cubism's revolutionary approach to form and space. Initiated by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in 1907-1908, Cubism dismantled and redefined established conventions of representing the visual world by rejecting illusionistic post-Renaissance perspectival space and the imitation of surrounding forms. The Analytic Cubist phase, reaching its zenith around mid-1910, introduced artists to the planarity of overlapping frontal surfaces held together by a linear grid. The subsequent Synthetic Cubism phase, from 1912 to 1914, incorporated flatly painted synthesized shapes, abstract space, and "constructional" elements into compositions. These three aspects became foundational characteristics of abstract geometric art, which sought to purify art from vestiges of visual reality and focus on the inherent two-dimensional qualities of painting.

Throughout Europe and Russia, different stylistic expressions of geometric abstraction evolved. In the Netherlands, Piet Mondrian emerged as a key proponent of the geometric abstract language. Alongside members of the De Stijl group, such as Theo van Doesburg, Bart van der Leck, and Vilmos Huszár, Mondrian aimed to convey an "absolute reality" rooted in pure geometric forms underlying all existence. Mondrian's geometric style, known as "Neoplasticism," took shape between 1915 and 1920. He published the manifesto "Le Néoplasticisme" in that year and continued working in his characteristic geometric style for the next two and a half decades. Mondrian's compositions featured a geometric division of the canvas through black vertical and horizontal lines of varying thickness, complemented by blocks of primary colors, particularly blue, red, and yellow. The principles underlying De Stijl artists' work aligned with Mondrian's, with slight formal modifications reflecting their individual expressions.

In Russia, the language of geometric abstraction emerged in 1915 through the work of avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich, who termed his style "Suprematism." Malevich aimed to create nonobjective compositions of elemental forms floating in unstructured white space, aspiring to achieve "the absolute" or the higher spiritual reality he called the "fourth dimension." Concurrently, Vladimir Tatlin originated a new geometric abstract idiom known as "painterly reliefs" and later "counter-reliefs" between 1915 and 1917. These works consisted of assemblages using randomly found industrial materials, with their geometric forms dictated by inherent properties like wood, metal, or glass. Tatlin's principle of "the culture of materials" influenced the rise of the Russian avant-garde movement Constructivism (1918-1921), which explored geometric forms in both two and three dimensions. Notable practitioners of Constructivism included Liubov Popova, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and El Lissitzky. Lissitzky played a crucial role in transmitting Constructivism to Germany, where its principles influenced the teachings of the Bauhaus. Founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus became a vital advocate for geometric abstraction and experimental modern architecture during the 1920s, until its dissolution by the Nazis in 1933. The art faculty comprised distinguished painters of the time, including Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, Oskar Schlemmer, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers, all dedicated to the ideal of geometric purity as the most suitable expression of the modernist canon.

During the 1920s in France, the Art Deco style embraced geometric abstraction as its foundational principle, advocating for the widespread use of geometric forms for decorative purposes in the applied arts, architecture, and ornamentation. In the 1930s, Paris became a hub for geometric abstraction, drawing inspiration from its Synthetic Cubist origins and revolving around artistic groups like Cercle et Carré (1930) and later Abstraction-Création (1932). With the onset of World War II, the focus of geometric abstraction shifted to New York, where the American Abstract Artists group, including Burgoyne Diller and Ilya Bolotowsky, continued the tradition after its European counterparts Josef Albers (1933) and Piet Mondrian (1940) arrived. Noteworthy events like the exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art" (1936) organized by the Museum of Modern Art and the establishment of the Museum of Non-Objective Art (1939, now the Guggenheim) brought renewed prominence to the geometric tradition, although it had largely entered a mature phase. Nevertheless, its influence reached younger generations of artists, particularly impacting the Minimalist art movement of the 1960s. In Minimalism, pure geometric forms stripped to their austere essentials became the primary language of expression. Artists such as Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Dorothea Rockburne delved into the geometric tradition, transforming it into their own artistic vocabulary.