When one thinks of the term “pillaging”, one may often be reminded of the enforced depletion of resources during wartime. However, with the present rise of the repatriation of looted objects in the 21st century, the term takes on a vastly different meaning. The “pillaging” a nation of its cultural identity, a worship object of its ritual and ceremony, and postcolonial realities of its cultural sovereignty – all these remain possible in the present day as power dynamics remain between countries with a history of colonial legacy and those subjected to the colonial regime. Once agency erodes through the consequences of pillaging, whether it be the agency of a monolithic historical narrative or the agency of claiming provenance, whose agency is erased, restituted, or restored?

The Grand Egyptian Museum, for example, opened this year with the Rosetta Stone and the bust of Nefertiti remaining overseas. Beyond the museum, other spaces in which traces of these power dynamics still remain may be much more subtle. The curatorial practice that espouses a white cube-oriented dynamism may engage in an exorbitant, egregious perpetuation of the voiding worship objects of their function – akin to the cycle of looting, restitution, and repatriation. It is through the white-cube that believer-visitors are restrained from performing religious and spiritual practices despite the presence of their object of worship.

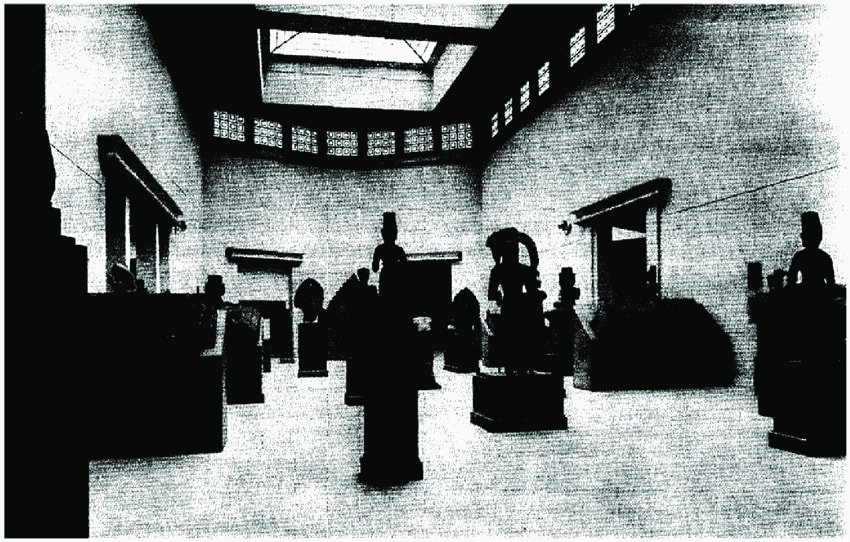

The influences of the white cube, since the post-War period, provided a distinctive context to which museums and galleries layout operates. One only needs to look at the Guimet Museum. In the post War-period, the Guimet Museum held one of the largest Asian artifacts outside of Asia and employed a “white cube” curatorial practice through its use of open space, white walls, tall ceilings, minimum panels and minute labels. According to art curator and scholar Shuchen Wang in Museum coloniality: displaying Asian art in the whitened context (2020), the Western cultural hegemony is crystalised by the erasure of colonial past of objects and the representation of the physical form of modernity. The demand for repatriation is, thus, nullified and new power struggles are raised. Such museography abided in the “elevation” of deities and worship objects of the “Other” to art in the West beyond a mere ethnographic specimen. And in so doing, such sacred icons and idolatry per se are diminished of their function.

The white-cube at the Musée Guimet in 1945, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet (MNAAG), France.

The white-cube at the Musée Guimet in 2001, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet (MNAAG), France.

Museum coloniality and the white cube within the Thai context is quite different than those Wang may have referred to. Thailand, indeed, was never colonised. However, the country may have arguably faced cryptocolonisation. According to anthropologist Michael Herzfeld in The Crypto-Colonial Dilemmas of Rattanakosin Island (2012) and Thailand in a Larger Universe: The Lingering Consequences of Crypto Colonialism (2017), Herzfeld posited that colonial elements were incorporated in local Thai governance, which reflects an ambiguity in control and adaptation that characterised the Thai identity of today.

In Śūnyatā, which takes from the Sanskrit term for “emptiness”, the exhibition questions the (ir)relevance of Thai contemporary art in the context of museum coloniality with Golden Boy, a recently repatriated “Thai” statue which stands at the National Museum Bangkok today, as the point of departure. In Buddhism, Śūnyatā is an extension of Anattā, or the non-self. Similarly, the exhibition does not aim to reinterpret any particular, individual repatriated object of worship but rather seeks to question the ecosystem in which museum coloniality operates which begets the devalorisation or nullification of worship objects as a whole. The choice of a Sanskrit terminology speaks to the Thai national identity that utilises language as a tool for the facilitation of class consciousness, with Pali and Sanskrit being associated with aristocracy and nobility, and local dialects, the marginalised and minorities. The exhibition, however, witnesses the display of historically noble headdresses and adornments on everyday people; which provides further semantic and allegoric juxtaposition of the Thai national identity birthed out of sociopolitical pressures for sovereignty in the past.

Through the selection of two Thai emerging artists Vayupad Rattanapet and Tanakrit Polngam, the exhibition seeks to reconcile juxtapositions of the institutionalised Thai national identity in arts and culture, and by extension, belief systems that were informed and contextualised somewhat by the nation’s history of cryptocolonialism.

Through our Artists Talk entitled Niras Vilas: The Journey of Thai Contemporary Art Through the Looking Glass, joined by Nakrob Moonmanas, Vayupad Ruttanapet, and Tanakrit Polngam, the exhibition is further explored through the overarching themes of Thainess, agency, perspectival narratives, artistic valorisation, and the historical Westernisation of curatorial practices.

Written by Kamori Osthananda

Images: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai